What Exactly Do You Want?

The Art of Wanting Things (Precisely)

A computer runs programs. It will do exactly what you tell it to do. Not what you meant. Not what you assumed. Not what any reasonable creature would infer from context. What you said (in code).

When you think about it, it’s rather refreshing, and safe. The computer is perhaps the only entity in the universe that truly listens without judgment, interpretation, or the assumption that you must have meant something sensible. It is the world’s most obedient servant, which turns out to be both a blessing and sometimes, often correlated to the programmer’s sleep and blood sugar levels, a curse.

The Hidden Universe in Simple Tasks

Simple things, it turns out, are rarely simple. They are merely familiar. And familiarity is the great enemy of observation.

When a human says “make me a sandwich,” they are not issuing a simple instruction. They are deploying centuries of shared cultural understanding, decades of personal preference, and an implicit trust that the listener shares enough context to fill in the gaps. “Make me a sandwich” is shorthand for a document that would, if written out in full, run to several pages and could include philosophical positions regarding the optimal structural integrity of tomatoes for culinary use.

Computers, unfortunately, did not attend the same cultural briefings. They arrived from somewhere else entirely, and they are very literal about everything. They have all the worldly wisdom of a rock, though, that’s unfair to rocks, which at least know which way is down.

This is not a limitation. This is a feature disguised as an inconvenience, because when you must explain every tiny thing and simple step, you discover what you actually want. All those hidden decisions and assumptions, everything you took for granted and never noticed because it happened automatically, suddenly commands attention. The fog of familiarity lifts, and you see the machinery underneath.

This is what communicating with a computer asks of us: to take the familiar and make it strange again, so that we can see it clearly enough to explain it. To account for any and all possibilities, exhaustively.

The Gentle Art of Breaking Things Apart

Anyone who studies complex systems eventually discovers decomposition: when facing something large and confusing, break it into smaller and less confusing pieces. It’s not always obvious where to make the breaks, and some divisions work better than others, which is what makes it somewhat of an art.

Take “cleaning the house.” This is not a task, it’s a category of tasks, three smaller obligations wearing a trench coat and pretending to be one. Under it we find an alarming number of smaller tasks, each one perfectly willing to spawn sub-tasks of its own.

Each of these smaller tasks is manageable. Some are even pleasant. The terror of “cleaning the house” can dissolve into a collection of modest, achievable steps, each one small enough to contemplate without despair.

This is what programmers do all day. They receive large, vague problems (“make the website faster,” “fix the bug,” “build me something that does the thing”) and once the need is understood, their first job is always the same: break it down. Find the edges. Identify the pieces. Transform the impossible into a sequence of merely difficult steps.

The skill is not in any individual step. The skill is in knowing how to divide, and where to cut.

Journeys and Outcomes

There are two ways to tell your taxi driver to get you to the airport.

The first is to provide directions: “Turn left at the church, go straight for two miles, take the third exit at the roundabout, and follow the signs.” This is a process, a sequence of steps that, if followed correctly, will eventually deposit you at your destination, assuming you counted the exits right and the landmarks haven’t been demolished.

The second is to state the goal: “Please get me to the airport.” This is an outcome, a description of where you want to end up, leaving the how to someone else’s discretion.

Both are valid and have their uses. Knowing which one to deploy separates tolerable communicators from good ones.

If you are giving directions to a human with a working knowledge of the town, the outcome ought to be sufficient. They know landmarks. They can adapt. If they encounter construction, they will find a detour rather than sitting motionless in front of an orange cone.

If you’re giving directions to a very literal entity (a computer, say, or a robot vacuum) the process becomes necessary. They need the steps because they cannot invent alternatives.

Even with computers, more so with AI agents, you can specify outcomes. You don’t need to tell the computer how to do it. You just describe what you want, and the computer figures out the rest.

Part of learning to program is learning which kind of instruction is appropriate when, and learning to recognise when you’ve been giving process instructions for a problem that really needs an outcome, or vice versa. Give it a try:

The Edges of Maps

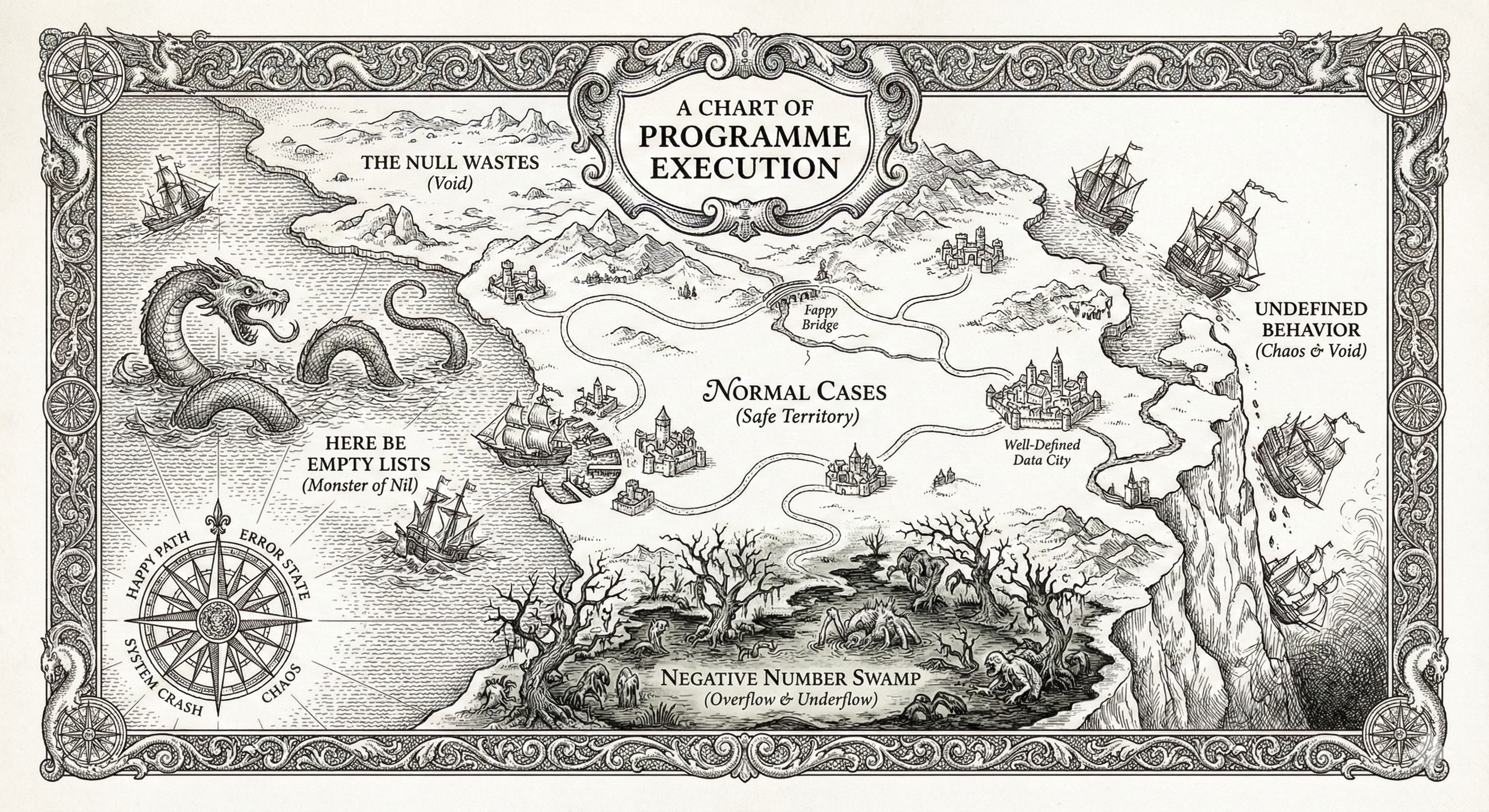

Now we meet edge cases: programmer slang for “the weird stuff that happens at the boundaries of what we normally expect.” Old maps used to write “Here be dragons” at the edges of the known world. Programmers write “TODO: handle this later” and then, since they are not computers, forget.

Back to the sandwich. We have been assuming that all the necessary ingredients are available. But what if there is no bread?

A human, faced with breadlessness, might suggest crackers, or toast, or the radical notion of just eating the peanut butter with a spoon. A human understands that the goal is sustenance and the method is flexible.

A computer, given instructions that assume the existence of bread, may simply stop. Or crash. Or, in more creative failures, attempt to spread peanut butter on the kitchen counter or the notes in the drawer. Computers have no sense of absurdity.

Edge cases are the places where our assumptions fail. They are the “what ifs” that we didn’t think about because we were too busy imagining the normal case. Common examples:

- What if there are no items to sort?

- What if someone enters their age as negative?

- What if the network goes down halfway through?

- What if two people try to book the same seat at basically the same instant?

- What if the user decides to paste the entire works of Shakespeare into the “phone number” field?

The computer does not judge these situations as “weird.” The computer does not have categories for normal and abnormal, reasonable and absurd. The computer simply encounters them and does something, often something surprisingly wrong, unless you have planned ahead.

Planning ahead means asking yourself: “What else could go wrong?”

This sounds pessimistic, but it’s actually the purest form of care. Good programmers spend a remarkable amount of time imagining failure. They think about empty lists and full disks and users who click buttons seventeen times in rapid succession because the screen froze. They think about time zones and leap years and that one day in 1752 that technically didn’t exist.

They think about the edges of the map, because that is where the monsters live. And then, they write instructions for what to do when the monsters appear.

The Programmer’s First Lesson

This brings us to the fundamental insight that underlies all programming:

You must know what you want before you can ask for it.

This sounds obvious. Yet it’s surprisingly difficult, because “what you want” tends to hide inside assumptions, habits, and cultural contexts you never noticed until you tried to explain them to someone who shares none of your background. We are, most of us, strangers to our own desires, until forced to articulate them precisely.

Programming is not as much about computers as people assume. It’s the articulation of a skill useful everywhere: precise thinking. The machine is merely the canvas and the brushes. The art happens between your ears.

When you learn to break problems into pieces, you become better at tackling any complex challenge.

When you learn to specify outcomes vs. processes, you communicate more clearly with humans and machines alike.

When you learn to anticipate edge cases, you become better at planning, at risk assessment, at noticing the gaps in your own understanding.

The computer is just the training ground. The real benefit of learning to program is the way your mind changes.

And the first step, before syntax, algorithms, command lines or any technical apparatus, is to ask yourself—with genuine curiosity and a polite unwillingness to accept the first answer:

What, exactly, do I really want?

Next: Now that we know what we want to say, we need to understand who we’re saying it to. The computer, it turns out, has a very particular way of seeing the world.