Talk to the Machine

On Talking to Things That Listen Too Well

You’re learning a new language, but this one has no idioms, no context, no body language, no tone. Every sentence means exactly what it says. “I could eat a horse” means you have the physical capacity to consume an equine. Sarcasm is impossible. Subtext doesn’t exist.

You must say precisely what you mean, because nothing else will be understood. This is the only language computers speak.

You’re a tour guide, and your tourist has just arrived from a planet with no atmosphere, no gravity, and no concept of “walking.” They’re brilliant. They’ve mastered interstellar travel. But they’ve never seen stairs. You point up and say “go to the second floor.” They hover in place, waiting. What’s a floor? What’s “up”? What does “go” mean when you have no legs?

Computers aren’t stupid. They just have no shared context with you. Not yet, anyway.

Imagine hiring someone who does exactly what you ask, never takes shortcuts, never uses judgment, and never goes home. You tell them to count the beans in a jar. They count every bean. You tell them to sort the mail. They sort it precisely as instructed, even if that means putting urgent letters at the bottom because you forgot to mention priority.

Tireless, accurate, and utterly incapable of reading between the lines. Congratulations. You’ve just hired a computer.

A musician sight-reading sheet music doesn’t interpret the composer’s “intent.” They play what’s written. If the composer wrote a wrong note, the musician plays the wrong note. The page has no room for “you know what I meant.”

Programming is writing sheet music for a machine that plays at the speed of light, never gets tired, and never, ever improvises.

Every fairy tale warns about wishes that come true too literally. The genie gives you exactly what you asked for, not what you wanted.

Programming is casting spells in a world where magic is real but irony doesn’t exist. Your words have power, when spoken in an exact order. They also have consequences.

The Most Literal Listener in the Universe

Computers today are magnificently complex, their inner workings too vast for anyone to completely comprehend. They are also spectacularly stupid. They have the reasoning capability of a rock.

This “stupid” machine is also reproducing my words, displaying it on your screen, managing the power to your devices, and helps fly airplanes and run hospitals. So is it really stupid?

The answer is hidden behind a lot of math, and many layers of abstraction - a computer does exactly what you tell it to do. Not what you meant. Not what any reasonable person would have understood. Exactly what you said. (Or, if you’re talking to an LLM, mostly sorta what you said.)

Programming Is Just Giving Instructions

If you strip away all the Matrix-style green text on black screens, all the complex diagrams and jargon exchanged over coffee, at its core, programming is simply telling a computer what to do.

That’s it. That’s the whole thing.

You already know how to give instructions. You do it all the time!

- When you follow a recipe, you’re executing a program that someone else wrote

- When you give someone directions to a restaurant, you’re programming their route

- When you select food from a menu, you are choosing from a set of typed objects

The only difference (and it is rather significant,) is that computers have absolutely zero common sense. They cannot fill in gaps. They cannot see the obviously relevant thing unless programmed to. They cannot “figure out what was meant”, especially with the many obvious things we leave unsaid. (Although with LLMs, they can pretend to, decently well.)

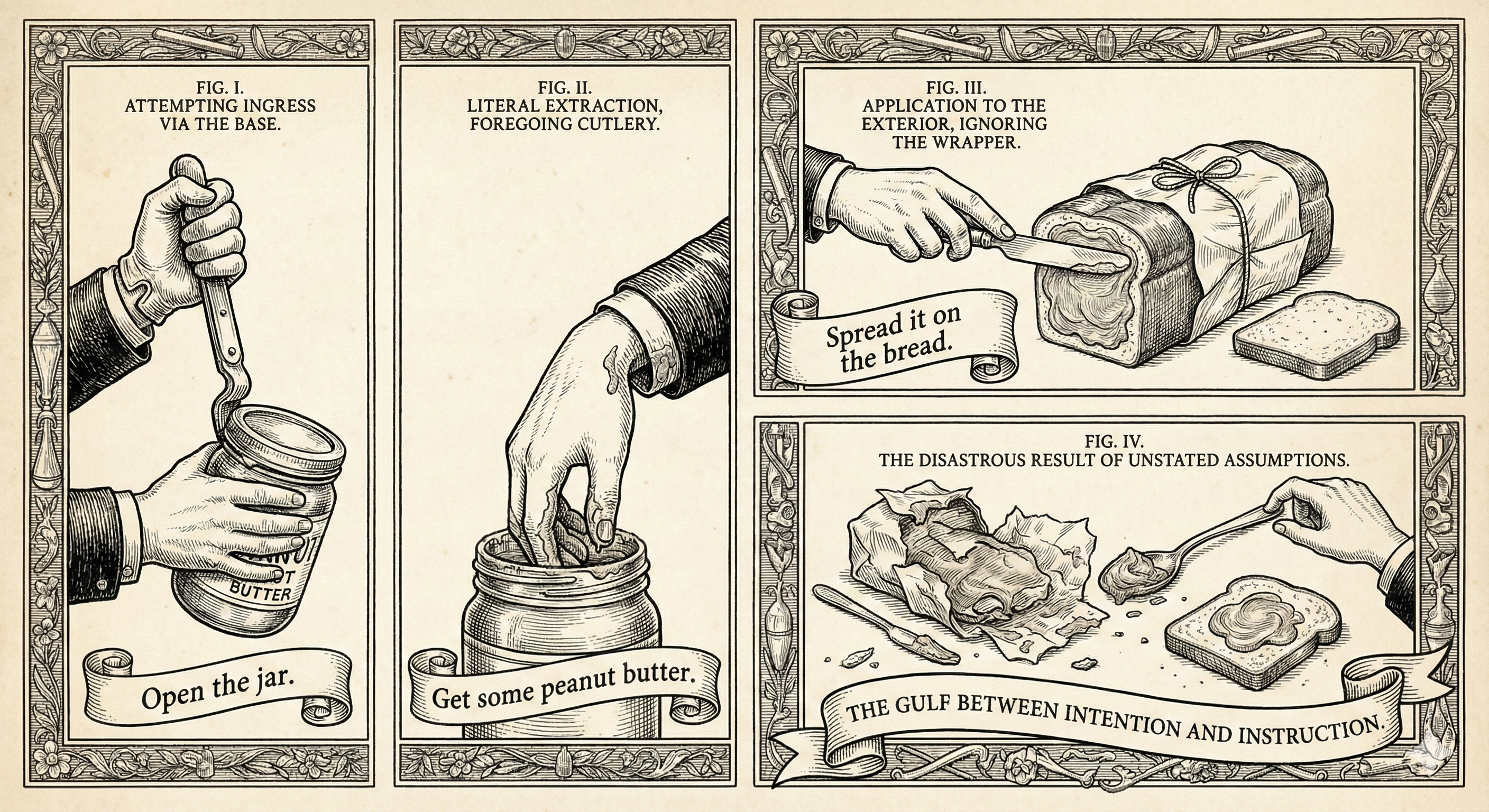

The Peanut Butter Sandwich Problem

Here’s an experiment loved by parents and professors alike, because it demonstrates the problem so perfectly that students often laugh at first, and then repeated frustration drives the point home.

The objective: explain how to make a peanut butter sandwich, as the teacher carries out your instructions.

The teacher pretends to be someone who has never seen a sandwich. Or peanut butter. Or bread. Or a jar. Also, they take every single word you say completely literally.

You might start with: “Open the jar of peanut butter.”

They pick up the jar and stare at it. Nothing happens. You didn’t tell them how to open it. Twist the lid? Which way? How hard? You didn’t say.

Okay, you try again: “Twist the lid counterclockwise until it comes off.”

They twist the lid, but they’re using both hands while they do it, so both the jar and the lid are rotating together. Nothing opens. You didn’t tell them to hold the jar steady with one hand and twist the lid with the other.

You see where this is going. Every single assumption you make (that someone knows which hand to use, where the knife goes, what “spreading” means, how thick the layer should be) fails when dealing with something that has no context, no experience, no common sense.

This is programming. This is what you’re signing up for.

And yes, it sounds incredibly frustrating. It’s also incredibly powerful.

The Upside of Literal-Mindedness

Once you learn to think and communicate precisely enough that a computer can understand you, once you can explain things to the universe’s most literal listener, something remarkable happens.

You can tell this machine to do something once, and it will do it perfectly, exactly the same way, a million times in a row. It will never get bored. It will never get tired. It will never say “But I thought you meant …”

Want to process a thousand photos? Tell the computer once; it does all thousand. Maybe even in parallel.

Want to check every day whether something has changed? Tell the computer once; it checks forever. As long as it’s running.

Want to calculate something complex? The computer doesn’t care if it’s tedious and takes a million steps. It’ll do every single one without complaining.

The precise communication and other skills you need to develop aren’t a bug in the process. They’re features. They force you to actually understand what you’re trying to do. They give you clarity, even without a computer.

The Tower of Abstraction

From where you stand, about to learn programming, it can feel like you are late to a party which started long ago.

For decades, we humans have been building a tower. Each generation of programmers has climbed atop the work of the previous generation, added a new floor, and rendered the lower floors comfortably invisible as part of the foundation.

At the bottom: electricity and transistors. Above that: machine code, then assembly language, then high-level languages like C, then even higher-level languages like Python and JavaScript. Each layer hides more machinery. Each layer says: “You don’t need to understand all of this. Here’s a simpler way to think about it.”

Today with LLMs, we have a new layer with AI coding agents and we can literally give instructions in language we use everyday. All we have to do now is learn how to think a little differently, and be able to appreciate what is happening under the hood, so we know how to tell the computer what to do more effectively.

This is why programming is learnable. You’re not starting from electricity. You’re starting from the penthouse, with an excellent view and central heating.

A New Kind of Conversation

For the first time in the history of this tower, you don’t need to learn a new language to hear the tower talk back to you.

AI coding assistants (tools like Claude Code, or Copilot, or Cursor) represent something unprecedented: an entity that understands what you mean, not just what you say. A translator that speaks both human and computer fluently.

In the before times, learning to program meant learning the computer’s language. Memorizing syntax. Understanding data structures. You had to adapt. Git gud and RTFM.

Now, the computer is a borderline sycophant.

You can describe what you want in plain English: “Make me a todo list app with confetti when I mark things done.” And the AI will translate that into actual code. You can point at an error and ask “what went wrong here?” and get an explanation in human terms. In fact, you could even just describe the outcomes you want, and let the AI agent take it from there.

However, the results can only be as good as your ask - you need to communicate clearly.

The AI is not a mind reader, even though it wants to be. It’s a very well-read colleague who has seen millions of programs and learned patterns from them. If you ask for something vague, you’ll get something vaguely correct. If you ask for something unclear, the AI will make assumptions, and those assumptions might not match yours.

You Already Have the Skills

You already know how to do this. Maybe not perfectly yet, but you have the foundation.

Every time you wondered how to best ask for help from someone else, you were thinking like a programmer. Every time you’ve assembled something from instructions, you were executing a program. Every time you’ve explained a process step by step (“first you do this, then you check if that happened, then you do the other thing”) you were describing an algorithm.

The skills and thinking transfer. You don’t need to learn an alien language. You only need to understand something you already do - communicate.

The computer is just a very particular audience. Like explaining things to a precocious five-year-old who asks “why?” about everything, remembers every word with perfect accuracy, and will hold you accountable to promises you forgot you made.

What Makes Programming Different

Some things are genuinely new and challenging:

Precision matters more than you’re used to. In human conversation, there’s a lot unsaid and taken for granted, which means we’re incredibly good at inferring meaning, filling in gaps, and understanding context. With computers, every gap you leave can cause a problem. Every ambiguity will bite you eventually.

Syntax is unforgiving. Human language is flexible. If you say “to store I went” people understand you meant “I went to the store.” Computers don’t. They have grammar rules (syntax), and breaking them means the computer can’t understand you at all. With modern tooling and coding agents this is less of an issue, but if you peek under the hood, it helps to know where the circuit breakers are.

You have to empathise with the computer’s capabilities. You can ask a human to “make this look better.” You cannot ask a computer that, at least not without explaining what “better” means in terms the computer can measure and act on.

Debugging is part of the process. It’s inevitable that something won’t work the way you expected. This isn’t failure. It’s a feedback loop. This is programming. Professional programmers spend huge amounts of their time figuring out why something didn’t work and fixing it. There used to be a lot of StackOverflow and Googling in between, but that’s so yesterday.

What You Don’t Need

Before we go on, let us clear up some common misconceptions:

You don’t need to be a “math person.” Programming is about solving problems using systems and steps, decomposition and decisions, not equations. If you can communicate your wants, you can program.

You don’t need to memorize everything or understand it all immediately. Professional programmers look things up constantly. Some things click into place only after you’ve used them a few times. That’s normal. The most important thing is to keep going!

The Most Important Thing

The logical thing that will matter more than anything else on this journey, is to keeping it going. How does one accomplish this? Curiosity.

If you’re curious about how things work, if you’re the kind of person who wonders “why did it do that?” or “what would happen if I tried this?”, you have the most important attribute for learning programming. (Or for learning anything else really.. Congratulations!)

Programming is, fundamentally (as far as this series is concerned), an act of communication. Communication is always lossy. Things will always go wrong, and you will always find a solution if you’re curious. Curious about what a computer can do, about how to solve a problem, about why your code didn’t work, and when you fix it, about what broke and why.

Frustration is a step towards great satisfaction. Confusion is a signal for directions of growth. Curiosity stays fueling you, and that’s what keeps you learning.

(Ironically, it is possible to learn helplessness, yet even then, curiosity sets us free.)

The Journey Ahead

This series will prepare you to program by reframing your communication with computers. Here’s the roadmap:

Ready?

So here we are. You’re about to learn to talk to the universe’s most literal listener. It will do exactly what you say, which means you’ll need to learn to say exactly what you mean.

You’ll get frustrated. That’s guaranteed. You’ll write code that doesn’t work, and you won’t know why, and you’ll want to give up.

But you’ll also experience that sublime satisfaction when something finally works. When you tell the computer to do something complex, and it does it, perfectly, exactly as you imagined. When you solve something that seemed impossible ten minutes ago. When you build something useful or beautiful or just plain interesting.

Programming is telling a computer what to do.

It’s easier than it looks from the outside, and harder than it looks once you start. But it’s absolutely learnable, and it’s worth learning.

The computer is waiting. It’s ready to listen. It will even help you along the way.

Now we just need to figure out what we want to say.

Next: Before we can tell the computer what to do, we need to figure out what we actually want.